unsupervised learning and autoencoders

During a hackaton I got a problem where we had very little labeled data (almost nothing at all) and no easy way to get more. I proposed a solution with an autoencoder, it is pretty stright-forward, but later I started wondering why so few uses this solution instead of trying to wrangle more labeled data (which usually are quite expensive). I believe it partly has something to do with the idea that real data do something magical with the input data, and partly that most users overfocus on what they want to get out of the network.

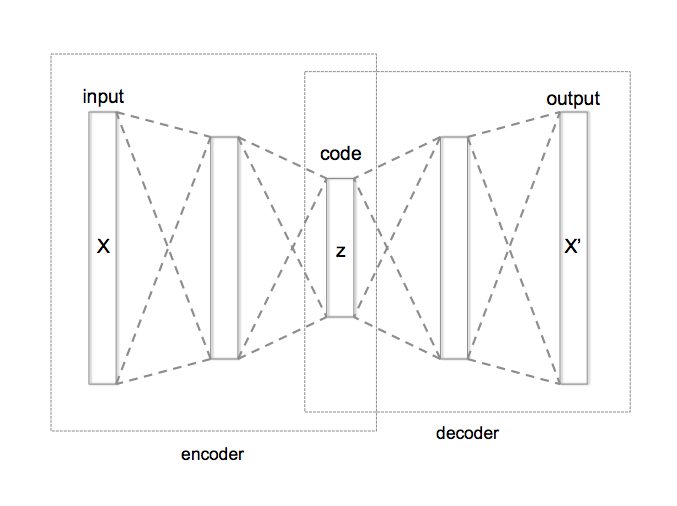

Figure 1: Autoencoder, consisting of five different layers. Input–hidden encodes and hidden–output decodes. (Wikimedia Commons/Chervinskii/Cc-by-sa 4.0)

Figure 1: Autoencoder, consisting of five different layers. Input–hidden encodes and hidden–output decodes. (Wikimedia Commons/Chervinskii/Cc-by-sa 4.0)

What an autoencoder do is to adapt its weights to make the best recreation for an observed set of data. The inner representation that will make this possible, that is recreate the observed data, is a sufficient approximation to the inner representation for some target vector from a later layer. It is not strictly the same, but it spans the same subspace. Backpropagating the errors from the later layers to the layer holding the inner representation could be (and often is) much longer, thus it is susceptible to the vanishing gradient problem.

The input in our two scenarios can be described as samples from the system under observation. That system has some function, but unknown to us, but it will be observable through the samples. If the system is continuous, differentiable, and observable, then there exist a learnable model for the system (although it may not be controllable).

An important point; the system isn't some random system, but the samples may be drawn according to some distribution. The samples lay on the manifold, that is only truthy values exists, and there may be no way to extend outside the manifold. To be able to analyze the encoding it is common practice to assume the inputs to be drawn at random from a unknown distribution, but that isn't quite correct.

Now assume the model is a neural net, and it has some smaller vector as an internal representation. That is, it has a smaller hidden layer. Because it can not fully encode the input space, it will try to recode the input into the best approximation, and this subspace will be some implementation of a manifold from the input space. The samples lay on the manifold, and the simplification is given by the loss.

Supervised learning

In supervised learning the network is trained with labeled data that tells the network what is the correct output $\mathbf{t}$, given an input vector $\mathbf{x}$, while the network gives $\mathbf{y}$.

\[\begin{equation} E = \operatorname{L} \left ( \mathbf{t}, \mathbf{y} \right ) \end{equation}\]where

- $\operatorname{L}$ – the cost function,

- $E$ – the loss for the target $\mathbf{t}$ and output $\mathbf{y}$,

- $\mathbf{t}$ – the target for the training sample, and

- $\mathbf{y}$ – the output from the network.

The input is known, but we must label each one of them to be able to learn anything. The labeled data is our target vector, but they are tedious to create, and often really expensive.

Autoencoder

An autoencoder takes an input vector $\mathbf{x}$, which is the target and is equal to input $\mathbf{t} \equiv \mathbf{x}$, and tries to recreate the input (or target) as the output $\mathbf{y}$. The loss is

\[\begin{equation} E = \operatorname{L} \left ( \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \right ) \end{equation}\]where

- $\operatorname{L}$ – the cost function,

- $E$ – the loss for the input $\mathbf{x}$ and output $\mathbf{y}$,

- $\mathbf{x}$ – the input to the network, and

- $\mathbf{y}$ – the output from the network.

The input is known, but so is also the target because it is the same as the input vector. If samples from the input space is easy to get, then it is simple to train an autoencoder.

Transfer learning

If there exist sufficient data in one domain, but not in another, then a neural network can be trained within the domain with sufficient data and retrained within the domain with insufficient data. Such retraining is referred to as transfer learning. The same can be done with an autoencoder.

If some network trained by unsupervised learning has the same hidden layer, with the same shape and location, then the actual loss backpropagated through the layers may be slightly different from the autoencoder, and the weights will be set slightly different. It will although span the same subspace, because it has the maximum information. The hidden layer (the bottleneck) of the autoencoder will try to optimize a subspace that resembles the same hidden layer for supervised learning if we had enough labeled data.

The same holds for transfer learning in general, it is the same subspace the hidden layers try to learn, and only the final layers adapts this to a specific target (or solution).

Discussion

By using an autoencoder it is possible to do massive initial training without labeled data, which is often a major hurdle. With ordinary supervised learning we need labeled data, which is expensive. When training with an autoencoder, that is not necessary, as the input samples themselves act as target values.

It may not be obvious, but the input to later layers comes from the layer creating the internal state, the bottleneck layer, and not from the final layer of the autoencoder.

After the initial training it is possible to train a final layer on the internal representation, which can be a vector with rank several order below the input layer. That reduces the necessary amount of labeled training samples, which may make it possible to model the problem with a neural network.

Training the autoencoder can also give loss that can be backpropagated into previous layers, thus being used for training outside the autoencoder itself. In those cases it will modify its own feature extractors, and optimize loss it can’t remove with its internal representation.

The loss goes very quickly to a zero mean for the entries that maps to a clean internal representation, and will thus vanish, but a residue error will persist from the autoencoder. It is that residue error that will drive adaptations in previous layers.

In this case the loss can be taken from the input layer of the autoencoder, as this is the target value. By doing so several layers of backpropagation can be skipped, and vanishing gradient avoided.

It is even possible to learn an autoencoder with several residual layers, where each layer uses a shared input layer. This kind of construct facilitate a quite fast convergence.

blog comments powered by Disqus